The Evolution of the Spot

The skate spot is the unsung hero of skateboarding, with a history as rich and diverse as that of skateboarding itself (the two, in fact, are often intertwined with one another). But what does the concept of a skate spot entail? And how did the skate spot as we know it come to exist? We here at Theories of Atlantis, ever the vigilant truthseekers, have tracked down and compiled the key figures and moments that played a role in shaping the modern day skate spot. As always, this is highly contentious and up for debate.

1970s - In search of a terrain to emulate surfing when the waves are flat, the Zephyr team stumbles across a number of banked schoolyards in the Los Angeles area. Several of these are heavily sessioned before skateboarding in empty backyard pools catches on, making them arguably some of the first (and longest lasting) street spots.

1984 - Lance Mountain pops out of a chimney and takes a skate down the street in The Bones Brigade Video Show. Though somewhat gimmicky in nature, Lance's trip sows the initial seeds of street skateboarding, as he skates off curb cuts, hits some natural transition, and even boardslides a double-sided curb (albeit before street planting over it).

1985 - Amidst skateboarding's infatuation with vert, Tommy Guerrero blazes the San Francisco hills in Powell Peralta's Future Primitive. This is one of the first all-street parts, and one of the first instances of skateboarding utilizing natural terrain, including downhills, double sided curbs, bank-to-curbs, and drops, as an act unto itself (rather than a substitute for another activity). As such, street skateboarding starts to assume an identity of its own separate from vert or surfing.

1987 - Street skateboarding in the mid-to-late eighties still heavily relied on surf-like motions, such as carving or launching, and these acts manifested themselves in spots like the China Banks or Fort Miley, until Natas Kaupas fully harnesses the power of the ollie in Santa Cruz's Wheels of Fire, going up and down curbs, off ledges, into stalls on benches, off bumps, and even over a trash can from flat. In doing so, he paves the way for future generations to look at hips, flat ledges, manual pads, bank-to-ledges, and curb-cuts in a new light.

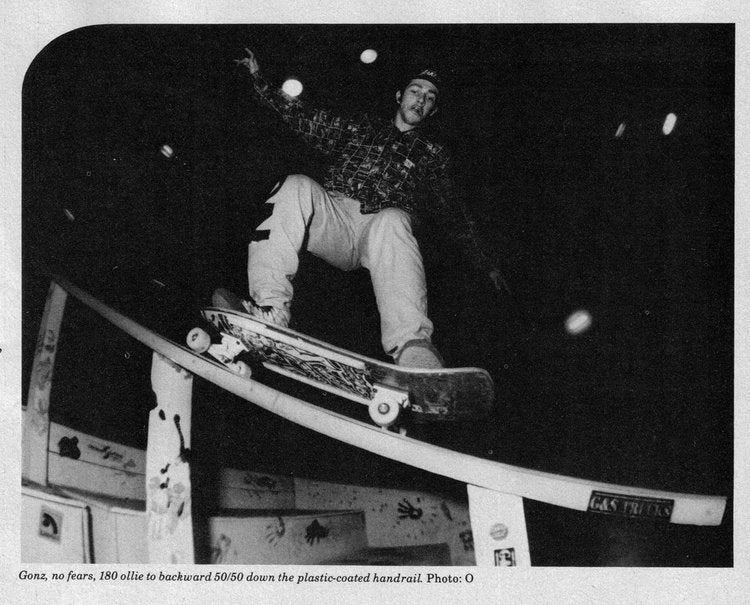

Across the country, Mark Gonzales starts experimenting with handrails in New York City with a boardslide down the smaller Brooklyn Banks rail, and a frontside boardslide and a 50-50 down another handrail. Photos dated 1987 also show Natas boardsliding circle rails and 50-50ing smaller, square rails.

1988 - In two short years, streetstyle contest obstacles went from jump ramps and slider bars to boxes and makeshift handrails.

1989 - Frankie Hill pushes handrail and gap skating to a new level, albeit with the help of a jump ramp, in Ban This. Meanwhile, skaters in San Francisco stumble upon a secluded pedestrian walkway with a concrete ledge running parallel to the stairs. Wade Speyer pops the spot's cherry with a crooked grind, and the hubba ledge is born. Finally, Matt Hensley and friends heavily session what appears to be the first street flatbar in Hokus Pokus.

1990 - Obviously a benchmark for modern skateboarding, Video Days also features some of the earliest examples of organically linking spots and lines together. In doing so, Mark Gonzales demonstrates the flow and rhythm in this part that sets the norm for street skateboarding. Many types of spots also make their first appearance in the video, including street gaps and kinked rails. By this point, the jump ramp is all but phased out of street skating, as are stalled ledge tricks from flat ground (a staple of early street skating).

1991 - The rapid technicalization of skateboarding pushes skateboarders to more isolated areas to learn and perfect new tricks. Nowhere is this more apparent than major metropolitan cities, where public spaces that were once only skated in passing become cultural epicenters. Thanks to their recognizable look, their wide variety of ledges and stairs, and their seclusion from pedestrian life, downtown plaza spots like LOVE Park, Pulaski Plaza, and Embarcadero become mainstays in the culture and remain the blueprint for a plaza spot to this day.

Around this time, we start to see the preexisting idea of spots pushed to the next level. Pat Duffy starts skating twenty stairs rails and Sean Sheffey ollies a full-length street gap.

1993 - As skateboarding's fixation on tech grows, spot selection takes a backseat to trick selection. Videos of the era mostly feature footage from curbs, parking lots, and schoolyards, though certain individuals, such as Kris Markovich and Jeremy Wray, take the effort to push the envelope of speed, style, and size.

1996 - Skateboarding awakes from its low-impact phase as if roused out of a drunken stupor. Though most of the acclaimed videos of the era, including Trilogy and Mouse, rely heavily on schoolyard footage and secluded ledge spots, we start to see more of an emphasis on the spot as more than a vehicle for a trick. Welcome to Hell features a number of out-of-the-ordinary handrails going around curves and through kinks, and Eastern Exposure 3, in particular, pushes skateboarding out of the schoolyards and back into the streets themselves, with a heavy emphasis on long lines in an urban environment. Here, we see skateboarders fully utilizing bank-to-walls, jersey barriers, propped-up grates over trash cans, bump-to-bars, and even cars. Ricky Oyola and co. also popularize the Philly step, a set of stairs skated like a ledge parallel to one's front door. The concept will be seen countless times in the future, most notably in San Francisco's 3-up, 3-down spot.

1998 - Handrails and gaps become king. Though the concept had already existed in some form with spots like the Carlsbad gap, the marquee spot becomes a mainstay with career breakers like El Toro, Clipper, Wilshire, and seemingly dozens more.

2000 - Skateboarding takes the first steps towards globalization. Waiting for the World gives the U.K. scene its first shine, and Barcelona footage starts to trickle into American videos. The unique architecture of these European cities starts to throw the traditional filming process for a spin. Eventually, it won't be enough to simply film an impressive trick; the spot has to be on-point, as well.

Jay Maldonado's La Luz presents a glimpse into the east coast scene. Bobby Puleo's approach to skateboarding, with a heavy emphasis on combing unseen neighborhoods and alleyways for quick-footed ledges and cellar doors, eventually becomes popular, pushing the idea of spot-hunting, as well as some of the very spots he skated, to cliché status. People don't seek out spots because they aren't crusty, but rather, because of their inherent crust.

2004 - Static II continues in the vein of Eastern Exposure 3, though with an increased emphasis on skateboarding's growing globalization. In the midst of one of the most hammer-heavy periods in skateboarding's history, Stewart & co seek out unique combinations of bumps, ledges, and banks throughout streets the world over, furthering the concept of the spot taking precedence over the trick.

mid-2000s - Once loosely regulated, the unspoken rules around makeshift DIY obstacles grow stricter. Though some individuals manage to sneak in a few tricks on fabricated spots, we start to see fewer desks propped down apartment complex stairs, fewer clips from skatepark boxes, fewer bumps to angle iron ledges at existing spots, and fewer relevant Scientologists.

2007 - Tech skating picks back up and most everyone spends the mid-aughts (and their brand's travel budgets) filming in China's numerous marble plazas. Back in the United States, the Static III crew and Anthony Pappalardo foreshadow everyone's coming obsession with cliché "east coast" street skateboarding. Over time, wallies and pole jams will eventually bleed into contemporary skateboarding.

2008 - The Far East Skate Network drops Overground Broadcasting. The video leaves a lasting impression on viewers, thanks to the quick-footed approach to Japanese architecture on display that pushes the boundaries of what's traditional considered an "acceptable" spot. Unique transitions and ledge variations abound, and Gou Miyagi, in particular, grinds flatbars that go up, down, around corners, in circles, and into walls. Though the Western world fails to take notice, the FESN are ahead of their time, and by pushing the boundaries of what constitutes a spot, their unique approach will eventually bleed into mainstream skateboarding culture.

2009 - Jake Johnson breathes new life into wallrides and wallies, starting with his Mind Field part. Over the course of his career, he'll do them switch, nollie, down double sets, into tailslides, onto cars, and more, eventually popularizing the tricks and pushing the concept of a wallie or wallride spot into contemporary skateboarding. Johnson also does the infamous Battery Park ride-on grind switch, opening the door for variations of the trick and ride-on grind spots.

With the proliferation of YouTube and the ease of exchanging local videos between scenes, we start to see more of an emphasis on regional spots and architecture from all corners of the globe. The door is open for not just different spots, but different approaches to spots, which will eventually lead more people across the globe to look at their old spots in a new light and give preferential treatment to more aesthetically pleasing spots in terms of layout and background.

2010 - Case in point: heavily influenced by Takahiro Morita's work, Leo Valls takes a different approach that eventually loosens the criteria for what a spot is. Heavily contingent on wallies, banks, and repetitive spins, Valls occupies a sort of middle ground between traditional street skating and what could be described as "interpretive" skateboarding. Manuals no longer need to be done on manual pads, and something as simple as a planter to wallie over, a set of stairs skated oblong, or even smooth ground can be a spot if it looks good on film.

2013 - Thanks to the Sabotage movement and the revitalization of LOVE Park, we see a second coming of the plaza spot. Over the next several years, skateboarders in major metropolitan cities recognize and revere the role the plaza plays in their scenes, resulting in an upswing in footage from Chase Plaza, JKWON, Pulaski, Republique, Black Blocks, Peace Plaza, and even the fountain at EMB.

Bronze's second video, Solo Jazz, foreshadows a second coming of the New York skate scene and New York-esque spots, such as quick-footed spots, bump to bars, and wallrides mixed in with ledges, rails, and gaps.

2014 - Videos like cherry, Static IV, and Paych establish NYC as the new Barcelona, an "it" locale for skateboard pilgrimages and summer trips. These three videos, in particular, pushed the idea of using the streets as backdrop and (mostly) stayed out of safe spaces with no aesthetically pleasing characteristics, such as schoolyards, apartment complexes, and strip malls of LA.

What's more, cherry and, to a lesser extent, Static IV and Paych, features ride-on grinds, pole jams, and wallride spots in a heavier concentration than skateboarding has seen before. These spot selections will trickle down until they're seen as somewhat commonplace in mainstream skateboarding.

GX1000 starts popping grates again with a vengeance, launching onto ledges, over parking meters, and down gaps. The crew also takes a moment to remind everyone the hills are still a spot.

2015 - The west coast starts emulating the east coast. Guys like Ben Gore, Vincent Alvarez, and the WKND crew grow tired of the schoolyards and start scouring the Los Angeles area for cutty porch spots or back alleyways. In some cases, they're so successful that you wouldn't recognize the footage for Los Angeles footage until someone pointed it out to you.

Present day - If the early 90s was "anything goes" in regards to trick selection, the mid-to-late 2010s could be "anything goes" in regards to spot selection. Brought on in part by Instagram's increased presence in the media and coupled with an inventive approach to filming in an era when everyone is hyper-talented, we're seeing an influx in tricks once thought of as bottom rung. Chris Jones pushed the firecracker beyond novelty status in his Spirit Quest part, Max Palmer and the Atlantic Drifters take hippy jumps to odd, uncomfortable places, caveman tricks onto rails and hubbas are no longer just warm-ups, and even slappy variations are filmworthy. As these tricks become increasingly acceptable to film, people will find more obstacles to make their clips stand out. As such, the definition of a spot is loosened once more.

Satisfied? Did we miss anything? Let us know!

-ATM

1 comment

Hey man sooo cool my era is like 2012-2014/15